Trailers - Design & Build

D. SUSPENSION TYPES

“Springs? Who needs springs? I had a trailer for 10 years. It towed great. Low to the ground. Easy to load. It never had springs!” TRAILERS-How to Buy & Evaluate shows several examples of such trailers. “Of course we had to constantly re-weld the coupler, axle and all corners of the frame”. If you don’t mind this extra expense, bother and potential risk of inopportune failure, then no, you don’t need springs to make a trailer operate. The wheels still roll, it still hooks to the tow-car and your cargo can still be loaded. And there are plenty of trailers around without springs to support your conviction. But springs do make life easier for everybody-cargo, fellow drivers . . . and in the long run, even you.

The primary purpose of springs is to cushion the load fed into the frame of the trailer and subsequently the merchandise on top. If your cargo has little or no value, such as garbage, a trailer without suspension will certainly get you to the dump and probably back. On the other hand, if your cargo or trailer has value, you may want to reconsider and decide that springs are an important and necessary part of the trailer. Trailers with springs spend much less time in weld repair shops having fatigue cracks repaired than those without springs. If you already own a trailer without springs, an investment in a welder will quickly pay for itself. So will an investment in springs.

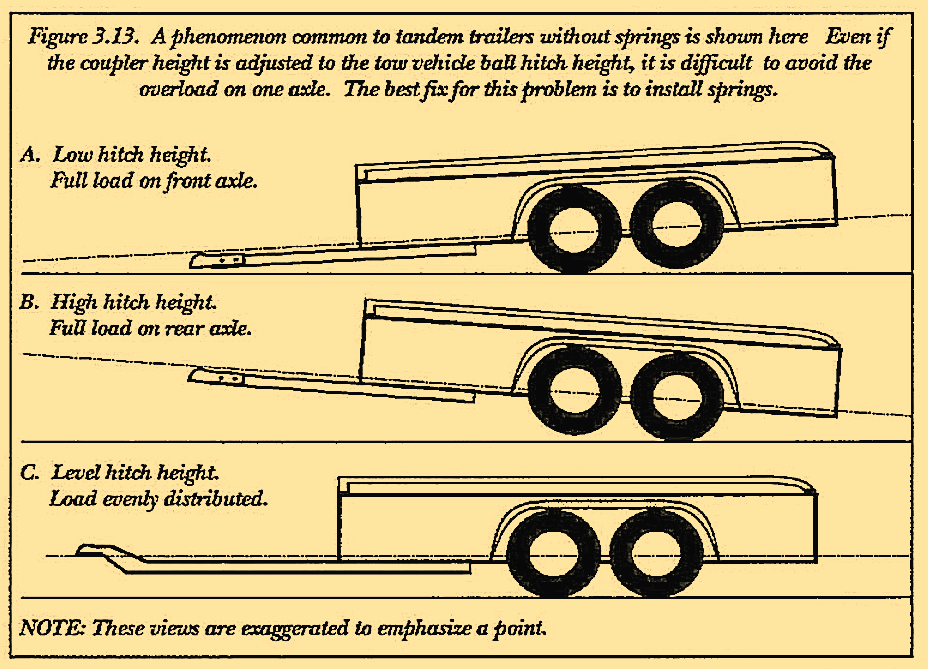

Tandem trailers, though, pose a special problem when built without springs. One axle or the other ends up being overloaded. This happens when a ball height too low pulls the nose of the trailer downward, thereby lifting the rear axle off the ground as in Figure 3.13. On the other hand, a hitch ball height too high, lifts the front axle off the ground. Even with a hitch ball height coordinated with the trailer coupling height, this see-saw continues on dips and rises in the road playing havoc with axle ratings, especially if axles are installed with the intent to carry only half the load. In reality, the axle sees one-half the load only part of the time and, unfortunately, ALL the load some of the time, as the weight shifts from front axle to back axle. The only solution to this see-saw is to install springs of some sort and there are several from which to choose.

Suspension—Leaf Springs

Until recently, trailer suspension systems in the U.S. have been pretty much standardized since trailers were first towed behind automobiles. Leaf springs, the product of least resistance, are and have been cheap and readily available from many junk yards in all shapes and sizes. Although the use of junk yard springs are seldom appropriate for manufactured trailers, the pattern stuck. And in light of few other options, trailer manufacturers found themselves requesting automotive springs for their creations. Hence, the unanimous swing to this suspension. Figure 3.14 illustrates the two general styles typically installed on new trailers. The standard two-eye springs are the same style as automotive springs and have been around the longest. The slipper style is a fairly recent development for trailers. Slipper springs are more economical and in some ways provide a gentler load transfer from spring to frame.

Selecting the correct springs is much easier if you know something about shapes, capacities, dimensions, what’s on the market and what works best where. A chart of typical spring capacities and their corresponding sizes is also shown in Figure 3.14. Except for very large capacities, the width for most trailer springs is 1-3/4-in. Standard two-eye springs have an eye to eye dimension of 26-in while the slipper is designed for an overall of about 25-in with the slipper length about 3-in to 4-in long, as the figure shows. Capacities of leaf springs are varied by changing the thickness of the material and the number of leaves, while retaining the same basic dimensions. These standardized dimensions certainly simplify installation.

Spring ratings are generally given in the number of pounds that will make two springs deflect 1-in, i.e. pounds per inch usually written as Ibs/in. This is a good basic number to use. Bear in mind that this 1-in deflection is from a static load. As you might guess, a slight overload will merely compress the spring more, to 1-1/4-in or 1-1/2-in, even 2-in. This is not a problem until the trailer is towed down the road where the effective load can double (or more) when a bump is hit. And, yes, when this occurs, it means the load is instantaneously twice or thrice the static load and the springs are compressed accordingly. If the load is within the capacity range, the springs merely compress. When the springs have plenty of room for deflection, the frame and cargo are cushioned. If the load is beyond that capacity, bottoming of the springs is a very likely scenario and the result is as if the trailer were unsprung; thus, the frame and cargo take a beating.